What does 'together' look like?

How do folks from diverse backgrounds and power dynamics come together to make media in a fair and equitable way?

As an interactive producer, I typically start at the end and work my way backward. If a client wants a 3D website, I scope requirements and figure out how to get there. Transdisciplinary research, on the other hand, starts with creating a surface area for collaborators to discuss, experiment, and build on each other. Figuring out what that looks like requires empathy, which is a process - not a product.

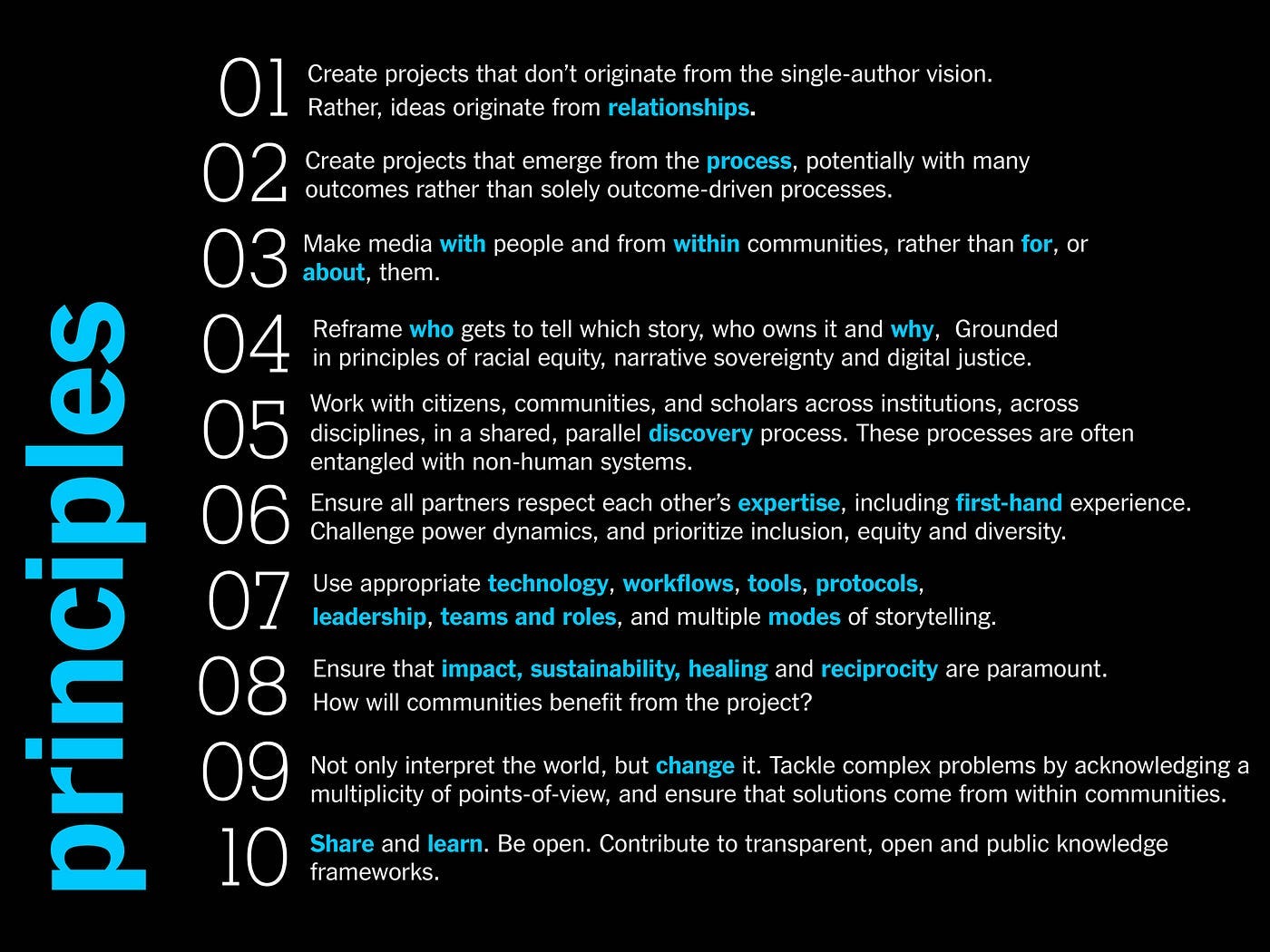

When I was first getting to know my friend Siwakorn Odochao (Swae), an indigenous coffee farmer, and Land Body Ecologies, a mental health and environmental research network looking at the experience of land trauma, I leaned heavily on MIT Open Documentary Lab’s Co-Creation Studio to inform everyday practices that build towards shared values.

“Such a practice suggests that social justice-centered values are embedded in the process of story creation itself. This, in turn, is ultimately about power in the story-making process: who holds it, how does it move through the production and distribution process, what is done with it, who benefits and who doesn’t.” - Collective Wisdom

Our goal was to develop mechanisms of care that ensure equitable process, ownership, and goals.

Collective Wisdom: Co-Creating Media for Equity and Justice

Ban Nong Tao Goals

Early on, we talked extensively about what we each hoped to achieve with this project. My main goal was to learn about different forms of farming. Vic from Invisible Flock, the anchor org in LBE, wanted to learn about land trauma and community resilience. Swae had the following goals for himself and his community:

Gather and share grassroots data directly from the community to the wider public

Empower the local community to protect land and get land rights

Share Karen culture with the world, especially city people

Show the existing connection between humans and forests

Over time, we all accepted that these goals might change, but in the end, I feel like we adopted each other’s goals.

Process

We began by setting intentions, which lays the foundation for shaping equitable process. Initially, I proposed a written contract that details this, but he preferred a more personal understanding. It makes sense. Especially considering how so many governments have broken indigenous treaties. In Pgak’yau culture, humans only have two main languages anyway: laughing and crying.

With guidance from “Collective Wisdom”, I wrote a list of questions and practices that I bookmarked in Chrome so it stayed top of mind.

Practices

Look for existing writings, research, and podcasts online before asking collaborators to take on the mental toll of educating. Use translation apps, come prepared with a basic idea, and ask for clarification.

Use ongoing discussion and agreement in place of written contracts. Many template contracts include total rights to IP, and many collaborators may (rightly) feel uncomfortable signing them.

If meetings are conducted in anyone’s non-native language, use short simple sentences and pauses between ideas. Ask for clarification and translate if needed.

Name common values and create a memorandum of understanding to share this context with each other and potential new partners.

Ask myself and each other the following guiding questions to ensure intentions stay aligned.

Guiding Questions

What are my gut instincts and biases?

Who is Responsible, Accountable, Consulted and Informed?

Am I inhabiting the Pgak’yau belief in slowness, listening, and observation?

Is there a power imbalance in how information is gathered or distributed?

The community goals are to share Karen culture broadly and to work towards land rights. Am I thinking about how this project can work towards those goals?

Does everyone feel like they can say no (without having to perform the no)

Am I open to ‘no’ or asking follow-up questions for clarity?

Am I asking questions I wouldn’t answer myself?

The last question was crucial while talking about climate grief and land rights. When working with indigenous communities facing displacement, what can we ethically ask and how can we prove ourselves worthy of that story? Am I asking someone to pick at their own stitches just so I can watch their insides spill out?

Potential Outcomes

We were lucky to get an extended amount of time to learn, ask, and listen, but how can we ensure that we work towards community goals? Or is this even wanted?

“Because a lot of people feel like they have gotten a sense of the trauma of Indigenous people for the first time. They really feel the need to make sure everybody knows about it. Who does that benefit? Not the Native [peoples]. [...] We all know what is going on there. People are more interested in solutions, also strengths, also a way forward, also honoring historical wrongs like treaties.” - Collective Wisdom

In the beginning, we outlined two potential surface areas for building strengths:

Relationships: Connect with indigenous groups that also use rotational farming practices or have similar land rights challenges to exchange notes and learn together. Also, connect with policymakers and share self-awareness guidelines that ensure they’re inhabiting Pgak’yau intentions of slowness and observation when working on conservation policies that may have far-reaching effects on indigenous communities.

Production: create research artifacts that capture lessons learned and can be shared widely on social media. Potentially create larger projects like the living documentary that allow communities to share grassroots data directly.

In the end, both surface areas were partially covered during the Land Body Ecologies Festival where Wellcome Trust supported a two-week exchange with policymakers, indigenous community members, and design researchers. Research artifacts were displayed for the public and the entire festival received great feedback.

Long Term Engagement

Now that the initial research is done, I’ve circled back to Ban Nong Tao goals and am thinking through:

What spaces and projects work towards land rights and preservation of the rotational farming system?

Unfortunately, Thailand’s dictatorship amplifies the challenge of gaining land rights. Pita, the left-leaning candidate who recently won the popular vote for Prime Minister, vowed to end lese majeste, a harsh law that penalizes criticism of the monarchy. His own indigenous cabinet member met with different communities in the North to tackle longstanding local issues. However, the military-stacked government just blocked his appointment and now, people everywhere are back to square one.

Many indigenous communities around the world face the same issue. They live in autocratic countries where gaining land rights will be an uphill battle.

Though my initial goal was to learn about growing food, rotational farming has taught me the significance of double utility systems. Rotational farming helps both people and forest in one go. It sustains communities with food, gives forests the ability to self-regenerate, and ensures clean air for all. However, without legal rights and economic security, this cycle comes to a halt.

As for the long-term vision of this collaboration, I don’t know, but my immediate focus is on exploring how legal rights to media created in the community can be shared. Some mechanisms:

Partial Common Ownership: a new evolving system that allows artists, communities and holders of art to create structures of shared ownership and distribution of value that better reflects those living relationships. PCOArt allows artists to embed the individual commitments their art may have to specific communities, causes and organisations into the ownership and value distribution model that underwrites the circulation of their work. Contrary to the traditional ownership model that privileges a single creator (the artist) and an exclusive owner of art (the collector), PCOArt offers a system for recognising the legal and economic status of a plurality of stakeholders and thus allowing art to perform its values not just symbolically but also operationally and materially.

Creative Commons: a licensing framework that enables creators to share their work while retaining specific rights. It offers a flexible range of licenses that allow authors to specify how their creations can be used, shared, and adapted by others. This approach fosters collaboration, encourages innovation, and supports a more open and accessible digital landscape by providing a legal structure for sharing and building upon creative content without the traditional limitations of copyright.

Biodiversity credits: Not directly connected to media but currently researching how these are quantified, especially for areas like Ban Nong Tao that aren’t expansive enough for carbon credits but have a beautiful array of different ecosystems. In Pgak’yau culture, each particular kind of ecosystem is a character. A tall mountain with a stream running through has a specific name, and a shorter mountain with tall trees has a specific name. I'd love to see how a community-led biodiversity credit system based on Pgak'yau spiritual practices could take shape.

Co-creating won’t immediately secure land rights or undo generations of injustice but maybe creating equitable structures for cooperation can work towards building and leaving renewable resources within the community.

Sources

Pathways and protocols - Screen Australia

Collective Wisdom - MIT Co-Creation Studio

The Voice, Choice, Action Framework - The Nature Conservancy